Noisy-channel coding theorem

In information theory, the noisy-channel coding theorem (sometimes Shannon's theorem), establishes that for any given degree of noise contamination of a communication channel, it is possible to communicate discrete data (digital information) nearly error-free up to a computable maximum rate through the channel. This result was presented by Claude Shannon in 1948 and was based in part on earlier work and ideas of Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley.

The Shannon limit or Shannon capacity of a communications channel is the theoretical maximum information transfer rate of the channel, for a particular noise level.

Contents |

Overview

Stated by Claude Shannon in 1948, the theorem describes the maximum possible efficiency of error-correcting methods versus levels of noise interference and data corruption. The theory doesn't describe how to construct the error-correcting method, it only tells us how good the best possible method can be. Shannon's theorem has wide-ranging applications in both communications and data storage. This theorem is of foundational importance to the modern field of information theory. Shannon only gave an outline of the proof. The first rigorous proof is due to Amiel Feinstein in 1954.

The Shannon theorem states that given a noisy channel with channel capacity C and information transmitted at a rate R, then if  there exist codes that allow the probability of error at the receiver to be made arbitrarily small. This means that, theoretically, it is possible to transmit information nearly without error at any rate below a limiting rate, C.

there exist codes that allow the probability of error at the receiver to be made arbitrarily small. This means that, theoretically, it is possible to transmit information nearly without error at any rate below a limiting rate, C.

The converse is also important. If  , an arbitrarily small probability of error is not achievable. All codes will have a probability of error greater than a certain positive minimal level, and this level increases as the rate increases. So, information cannot be guaranteed to be transmitted reliably across a channel at rates beyond the channel capacity. The theorem does not address the rare situation in which rate and capacity are equal.

, an arbitrarily small probability of error is not achievable. All codes will have a probability of error greater than a certain positive minimal level, and this level increases as the rate increases. So, information cannot be guaranteed to be transmitted reliably across a channel at rates beyond the channel capacity. The theorem does not address the rare situation in which rate and capacity are equal.

The channel capacity C can be calculated from the physical properties of a channel; for a band-limited channel with Gaussian noise, using the Shannon–Hartley theorem.

Simple schemes such as "send the message 3 times and use a best 2 out of 3 voting scheme if the copies differ" are inefficient error-correction methods, unable to asymptotically guarantee that a block of data can be communicated free of error. Advanced techniques such as Reed–Solomon codes and, more recently, turbo codes come much closer to reaching the theoretical Shannon limit, but at a cost of high computational complexity. Using low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes or turbo codes and with the computing power in today's digital signal processors, it is now possible to reach very close to the Shannon limit. In fact, it was shown that LDPC codes can reach within 0.0045 dB of the Shannon limit (for very long block lengths).[1]

Mathematical statement

Theorem (Shannon, 1948):

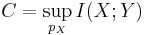

- 1. For every discrete memoryless channel, the channel capacity

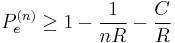

- has the following property. For any ε > 0 and R < C, for large enough N, there exists a code of length N and rate ≥ R and a decoding algorithm, such that the maximal probability of block error is ≤ ε.

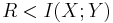

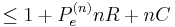

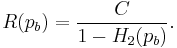

- 2. If a probability of bit error pb is acceptable, rates up to R(pb) are achievable, where

- and

is the binary entropy function

is the binary entropy function

- 3. For any pb, rates greater than R(pb) are not achievable.

(MacKay (2003), p. 162; cf Gallager (1968), ch.5; Cover and Thomas (1991), p. 198; Shannon (1948) thm. 11)

Outline of proof

As with several other major results in information theory, the proof of the noisy channel coding theorem includes an achievability result and a matching converse result. These two components serve to bound, in this case, the set of possible rates at which one can communicate over a noisy channel, and matching serves to show that these bounds are tight bounds.

The following outlines are only one set of many different styles available for study in information theory texts.

Achievability for discrete memoryless channels

This particular proof of achievability follows the style of proofs that make use of the asymptotic equipartition property (AEP). Another style can be found in information theory texts using error exponents.

Both types of proofs make use of a random coding argument where the codebook used across a channel is randomly constructed - this serves to reduce computational complexity while still proving the existence of a code satisfying a desired low probability of error at any data rate below the channel capacity.

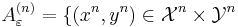

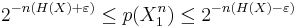

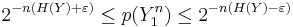

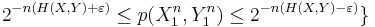

By an AEP-related argument, given a channel, length  strings of source symbols

strings of source symbols  , and length

, and length  strings of channel outputs

strings of channel outputs  , we can define a jointly typical set by the following:

, we can define a jointly typical set by the following:

We say that two sequences  và

và  are jointly typical if they lie in the jointly typical set defined above.

are jointly typical if they lie in the jointly typical set defined above.

Steps

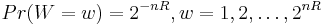

- In the style of the random coding argument, we randomly generate

codewords of length n from a probability distribution Q.

codewords of length n from a probability distribution Q. - This code is revealed to the sender and receiver. It is also assumed that one knows the transition matrix

for the channel being used.

for the channel being used. - A message W is chosen according to the uniform distribution on the set of codewords. That is,

.

. - The message W is sent across the channel.

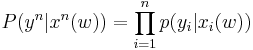

- The receiver receives a sequence according to

- Sending these codewords across the channel, we receive

, and decode to some source sequence if there exists exactly 1 codeword that is jointly typical with Y. If there are no jointly typical codewords, or if there are more than one, an error is declared. An error also occurs if a decoded codeword doesn't match the original codeword. This is called typical set decoding.

, and decode to some source sequence if there exists exactly 1 codeword that is jointly typical with Y. If there are no jointly typical codewords, or if there are more than one, an error is declared. An error also occurs if a decoded codeword doesn't match the original codeword. This is called typical set decoding.

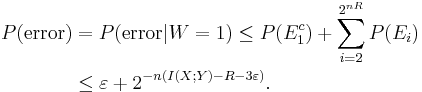

The probability of error of this scheme is divided into two parts:

- First, error can occur if no jointly typical X sequences are found for a received Y sequence

- Second, error can occur if an incorrect X sequence is jointly typical with a received Y sequence.

- By the randomness of the code construction, we can assume that the average probability of error averaged over all codes does not depend on the index sent. Thus, without loss of generality, we can assume W = 1.

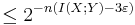

- From the joint AEP, we know that the probability that no jointly typical X exists goes to 0 as n grows large. We can bound this error probability by

.

.

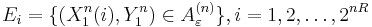

- Also from the joint AEP, we know the probability that a particular

and the

and the  resulting from W = 1 are jointly typical is

resulting from W = 1 are jointly typical is  .

.

Define:

as the event that message i is jointly typical with the sequence received when message 1 is sent.

We can observe that as  goes to infinity, if

goes to infinity, if  for the channel, the probability of error will go to 0.

for the channel, the probability of error will go to 0.

Finally, given that the average codebook is shown to be "good," we know that there exists a codebook whose performance is better than the average, and so satisfies our need for arbitrarily low error probability communicating across the noisy channel.

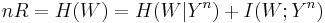

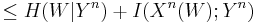

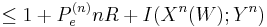

Weak converse for discrete memoryless channels

Suppose a code of  codewords. Let W be drawn uniformly over this set as an index. Let

codewords. Let W be drawn uniformly over this set as an index. Let  and

and  be the codewords and received codewords, respectively.

be the codewords and received codewords, respectively.

using identities involving entropy and mutual information

using identities involving entropy and mutual information since X is a function of W

since X is a function of W by the use of Fano's Inequality

by the use of Fano's Inequality by the fact that capacity is maximized mutual information.

by the fact that capacity is maximized mutual information.

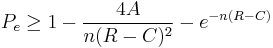

The result of these steps is that  . As the block length

. As the block length  goes to infinity, we obtain

goes to infinity, we obtain  is bounded away from 0 if R is greater than C - we can get arbitrarily low rates of error only if R is less than C.

is bounded away from 0 if R is greater than C - we can get arbitrarily low rates of error only if R is less than C.

Strong converse for discrete memoryless channels

A strong converse theorem, proven by Wolfowitz in 1957[2], states that,

for some finite positive constant  . While the weak converse states that the error probability is bounded away from zero as

. While the weak converse states that the error probability is bounded away from zero as  goes to infinity, the strong converse states that the error goes exponentially to 1. Thus,

goes to infinity, the strong converse states that the error goes exponentially to 1. Thus,  is a sharp threshold between perfectly reliable and completely unreliable communication.

is a sharp threshold between perfectly reliable and completely unreliable communication.

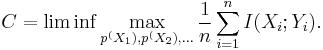

Channel coding theorem for non-stationary memoryless channels

We assume that the channel is memoryless, but its transition probabilities change with time, in a fashion known at the transmitter as well as the receiver.

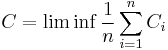

Then the channel capacity is given by

The maximum is attained at the capacity achieving distributions for each respective channel. That is,  where

where  is the capacity of the ith channel.

is the capacity of the ith channel.

Outline of the proof

The proof runs through in almost the same way as that of channel coding theorem. Achievability follows from random coding with each symbol chosen randomly from the capacity achieving distribution for that particular channel. Typicality arguments use the definition of typical sets for non-stationary sources defined in the asymptotic equipartition property article.

The technicality of lim inf comes into play when  does not converge.

does not converge.

See also

- Asymptotic equipartition property (AEP)

- Turbo code

- Fano's Inequality

- Shannon's source coding theorem

- Shannon–Hartley theorem

- Rate-distortion theory

Notes

- ^ Sae-Young Chung, G. David Forney, Jr., Thomas J. Richardson, and Rüdiger Urbanke, On the Design of Low-Density Parity-Check Codes within 0.0045 dB of the Shannon Limit, IEEE Communication Letters, vol. 5, pp.58-60, Feb. 2001. ISSN 1089-7798

- ^ Robert Gallager. Information Theory and Reliable Communication. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1968. ISBN 0-471-29048-3

References

- Claude E. Shannon, A Mathematical Theory of Communication Urbana, IL:University of Illinois Press, 1949 (reprinted 1998).

- Amiel Feinstein, A New basic theorem of information theory. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 4(4):2-22, 1954.

- Robert M. Fano, Transmission of information; a statistical theory of communications. Cambridge, Mass., M.I.T. Press, 1961. ISBN 0-262-06001-9

- Jacob Wolfowitz, The coding of messages subject to chance errors, Illinois J. Math., vol. 1, pp. 591–606, 1957.

- David J. C. MacKay. Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-64298-1

- Thomas Cover, Joy Thomas, Elements of Information Theory. New York, NY:John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-471-06259-6

External links

- On Shannon and Shannon's law

- Shannon's Noisy Channel Coding Theorem

- On-line textbook: Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, by David MacKay - gives an entertaining and thorough introduction to Shannon theory, including two proofs of the noisy-channel coding theorem. This text also discusses state-of-the-art methods from coding theory, such as low-density parity-check codes, and Turbo codes.

![H_2(p_b)=- \left[ p_b \log_2 {p_b} %2B (1-p_b) \log_2 ({1-p_b}) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/05fcf2d261f4976ba6067811e4274234.png)